From Prison to Purpose: How Jeanne d’Arc’s Journey Is Redefining Reintegration in Rwanda

When Jeanne d’Arc Nyirahabiyaremye was sentenced to seven years in prison, she thought her life was over. “When I was incarcerated, I felt as if my world had collapsed. I was hopeless and depressed,” she recalls.

Born in Kamembe, western Rwanda, Jeanne d’Arc had finished her university education, worked as a primary school teacher, and supported herself and her daughter after a difficult divorce. However, a desperate attempt to find a home for her children following her painful divorce resulted in her arrest and a seven-year prison sentence that profoundly changed her life.

At the time, she was a mother of newborn twin girls, whom she took with her to Nyamagabe Correctional Facility, and an adolescent daughter she left at home alone. Having to raise her 10-month-old twin daughters behind bars was a trauma she struggled to endure.

Inside the correctional facility, located in southern Rwanda, Jeanne d’Arc began to rebuild herself. Her background as a teacher quickly earned her a leadership role among inmates: she served two terms as the women inmates' representative, taught English and Swahili, coordinated education programmes, and helped others pursue their studies.

Still, the emotional toll was heavy. “I couldn’t sleep while I was in the correctional facility. I was like a zombie for the first two years. I only ate maize and didn’t want to eat anything else,” she says, adding that “the only thing that kept me alive was my twins.”

Jeanne d’Arc’s struggle was far from unique. Interpeace and partners’ studies have shown that many inmates experience serious mental health challenges, such as anger, guilt, anxiety, depression, and hopelessness, while incarcerated. Those convicted of grave offences, including genocide-related crimes or murder, often experience isolation, guilt, or hallucinations. Without adequate mental health support, these issues can slow rehabilitation and complicate reintegration. Some inmates continue to struggle with genocide ideology or denial, which can slow rehabilitation and pose risks to community cohesion and resilience efforts, and even fuel recidivism.

Today, less than a year after her release, Jeanne d’Arc is the founder and manager of Brighten Business Company Ltd, a local company that runs a hair and beauty salon and a training centre in Giheke Sector, Rusizi District — a place now filled with laughter, hair dryers, renewed hope, and the sound of second chances.

Healing Behind Bars

Jeanne d’Arc’s transformation is not an isolated case. Across Rwanda, similar healing and reintegration initiatives are changing lives behind bars. Hers and those of hundreds of others are part of a broader national effort to link rehabilitation with mental health and social reintegration.

Since 2022, Interpeace, in partnership with Dignity in Detention, Prison Fellowship Rwanda, and Haguruka, has collaborated with the Rwanda Correctional Service (RCS) and the Ministry of National Unity and Civic Engagement (MINUBUMWE) to enhance psychosocial support for inmates through the Societal Healing Programme, supported by the Government of Sweden.

Through this initiative, healing spaces based on sociotherapy have been introduced in several correctional facilities. In these small group sessions, inmates approaching release learn to confront past trauma, accept responsibility, rebuild trust, and find strength in resilience. The sessions also guide them in reconnecting with their families, communities, and even those they once harmed, paving the way for genuine forgiveness and reconciliation.

So far, over 600 inmates have participated, showing marked improvements in emotional stability and openness to reconciliation. A comparison of baseline and endline data survey confirms that acknowledgement of personal responsibility rose from 54% to 88%, while self-forgiveness improved by 31%.

A standardised psychosocial rehabilitation curriculum also helps inmates who cannot attend healing group sessions. It is delivered by trained correctional officers across all correctional facilities, helping inmates prepare for reintegration and rebuild relationships with families and communities.

“We were taught how to manage our emotions, take care of our mental health, and develop techniques to cope with challenges,” she recalls. “Facilitators often reminded us that our mental well-being is the most valuable thing we have, because there is no life without mental health.”

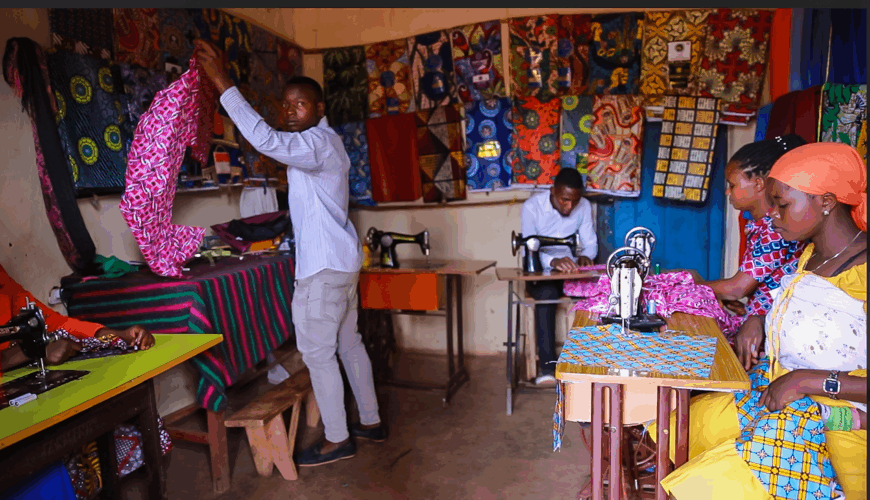

As part of their preparation, inmates receive vocational training in trades such as hairdressing, tailoring, welding, construction, masonry, mechanics, and handicrafts. This formal programme runs for six months, with graduates receiving official Rwanda Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Board certificates upon successful completion.

Close to 410 inmates graduated from TVET training in two years across four correctional facilities: Musanze, Nyamagabe, Ngoma, and Nyagatare.

Jeanne d’Arc chose hairdressing. She learned with zeal and enthusiasm, eventually earning her TVET Board certification, a milestone that laid the foundation for her new life. For her, these practical skills played a therapeutic role during incarceration and have helped her overcome unemployment challenges and reduce stigma after release.

A New Beginning

When Jeanne was released in January 2025, she was determined to start over. With the little savings she had earned from a nursery school teaching job she secured after her release, along with the skills she had gained, she opened her own beauty salon.

“I started the business here because there are no similar opportunities nearby. People would otherwise have to travel 30 minutes to get services,” she explains. Her salon offers Haircuts, braiding, washing, styling, nails, and makeup.

Her ambitions quickly grew. She transformed the salon into a training centre, offering young people practical skills and renewed hope to overcome challenges linked to unemployment and limited access to technical training opportunities. Brighten Business Company Ltd currently trains ten young apprentices who are working towards national certification under Rwanda’s TVET Board. But it’s more than a business — it’s a place full of laughter, energy, ambition, and renewed hope. Three of her first graduates now work alongside her at the salon, while others have secured jobs in the neighbourhood.

“I chose to focus on youth because they are the powerhouse of the country,” she says. “If they have skills, they can create jobs, support their families, and contribute to building our country.”

Her training extends beyond technical skills. Students learn English for client communication, sexual and reproductive health to prevent unplanned pregnancies, emotional regulation to handle workplace and daily life stress, and entrepreneurship to enable them to run their own businesses.

“We face many stressors in our daily lives. If a student has all the technical skills but can’t manage their emotions or treat clients with respect, the theory becomes meaningless. Teaching social and emotional skills is my way of giving back — those skills helped me the most in my journey of reintegration,” she says with conviction.

Redefining Reintegration

Today, Jeanne d’Arc is a respected member of her community. Her determination and positive example even earned her a teaching position at a local secondary school in Nyamasheke District. She now divides her time between running her company and teaching, and she plans to expand her business to create more training opportunities for women and youth.

Jeanne d’Arc’s journey from incarceration to empowerment shows the human face of rehabilitation — how restoring dignity, skills, and mental well-being can transform not only individuals but entire communities.

She deplores that stigma, community rejection, and being judged by one’s past remain major hurdles for former prisoners. Her message to society is simple but urgent:

“Don’t judge people by their past. Incarceration doesn’t take away your abilities, skills, or knowledge. Everyone deserves a second chance.”